THE RADICAL PLEASURE OF LETTING GO

– An interview with Ben Russell –

Watching a short film of Ben Russell is an experience. His films not only show a diverse range of psychedelic trips and transcending rites, they mostly turn out as a trip through your own psyche as well. Combined with subtle reflections on reality and societies throughout the whole world, his films will probably leave you speechless afterwards. Mister Motley talks with Russell about altered realities, having a physical body and his experiences in French Polynesia, where he just went to shoot his new film.

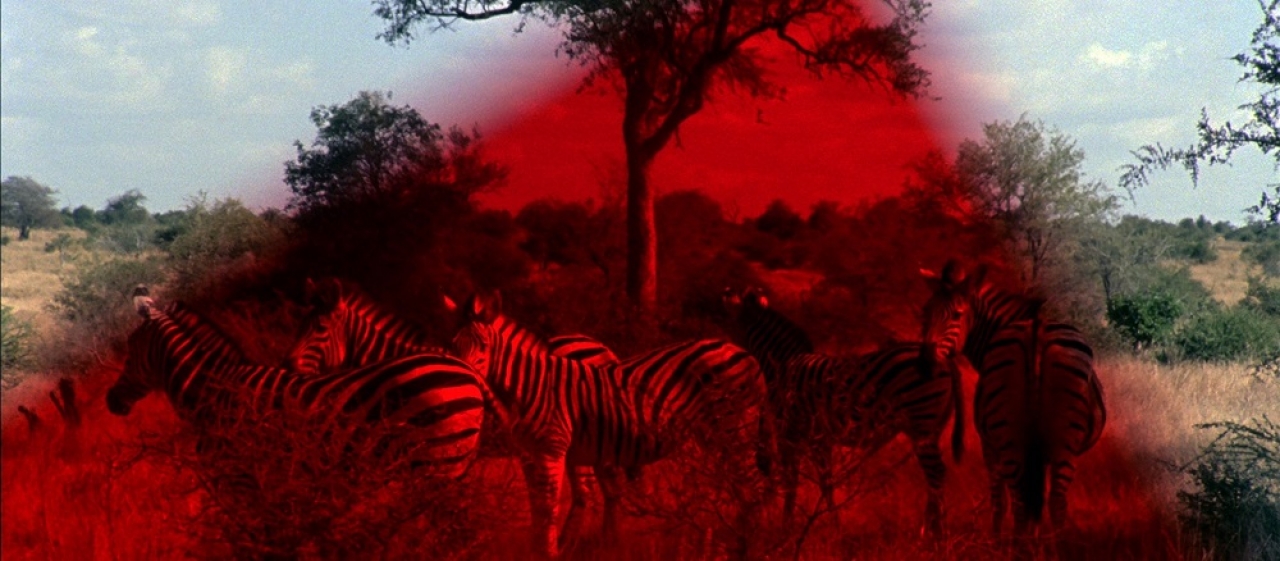

Mathieu Janssen (MJ): In your films you deal a lot with altered realities, like trips, dreams, stories, myths and transcending rituals. A very clear example is of course your Trypps series; seven short films about different psychedelic journeys. In Trypps #7 (Badlands) for instance, we see a long-take of a young woman that just took LSD. Why are you so fascinated by other realities?

Ben Russell (BR): I’m just looking for clues as to how to exist in this world – and it seems like there’s a great deal to be learned once we start to pull back the veil. I look towards cinema as a tool for bringing us closer to that which can’t be shown – to the trance state, the unconscious self, the subconscious world or the dream state.

MJ: The visualization of the inner human?

BR: I don’t know if it’s a visualization, necessarily – it’s more about the construction of another kind of space that runs parallel to the one we already know. When I make a film, I want to build a world for the audience to inhabit, one that might have the same characteristics as a trance state. I arrived at this idea sometime in the late 90s / early 00s while in attendance at a mess of crazy and visceral experimental noise concerts. Experiencing this made me realize that this was the sort of thing I wanted to produce in cinema: a space that could produce an active and engaged viewer and doesn’t leave them to just passively absorb something.

MJ: In your films you work a lot with mirrors and filters. Like when we watch the woman taking LSD, we realize halfway through the film that we’ve been watching her through a mirror. You always seem to suggest that even when we think we see reality, we are probably wrong and that everything is just a reflection of a reflection. Is there even such a thing as reality?

BR: Sure.

MJ: And can we see it?

BR: We can see a version of it – and then we can find another version through cinema which, strictly speaking, is a two dimensional simulation of a three dimensional form. Cinema suffers when it is asked to be a representation and I want cinema to be great – so I try to make films that are different from what we experience in the real world. Take Black and White Trypps Number Three for example – on the surface, it is a film of a concert of a noise band called Lightning Bolt. On its own, the concert experience is radical – it’s totally exciting and there’s nothing I could record that would compete with the actual experience. The film that came out of that experience had to be something else, it had to be something other than what it was. The world is already remarkable and complex – I make use of its reality but try hard not to reproduce it.

MJ: You use the beauty of reality to create something new?

BR: Yes, but I would never use the word “beauty.”

MJ: Why not?

BR: Beauty has already arrived – it doesn’t need me to make it better. On my recent trip to Polynesia I spent a lot of time thinking about beauty as both concept and action – I mean, I love a good sunset and the sunsets there are totally radical. They offer everything. Without fail, every time there was a sunset I would set up a camera to film it and be struck by the realization of how lesser my resulting image would be compared to what was unfolding in front of me. There was nothing I could add – I could only borrow, steal.

Said differently, one of the problems with beauty is that it doesn’t have any tension. It is already whole, complete. The kind of cinema that I’m after is a cinema of openness and uncertainty, one that isn’t immediately legible as to what it is. I want a cinema that has to sort itself out just as we try to sort ourselves out in relation to it. Beauty is just an image – we take it and move on.

MJ: Can you tell me more about what you experience at these noise concerts?

BR: It was the experience of having a body, of being a body. Of being a mobile subject acted upon by sound, movement and energy. Of being a participant who is also briefly a group which is also a community.

MJ: I can imagine you’re losing the control over yourself. Do you think that is scary?

BR: Yes! But it’s scary-exciting. The terror of letting go is very close to the radical pleasure of letting go. It’s less a loss of control as it is an experience of becoming a totally embodied subject.

MJ: What do you mean with ’embodied subject’?

BR: Being aware of yourself as a self. Being conscious of the fact that you’re perceiving, absorbing, engaging and processing in a way that is both active and unconscious at the same time. Most of the time, those of us who have bodies – which is all of us – are not thinking about our breath. Yoga and meditation tells us to think about our breathing, to be aware of how oxygen enters and exits our body. Embodiment asks us to give the same attention to the light that arrives at our optic nerves or to those sounds echoing in our skull from two different sides of our head. To be an embodied subject is to be active and attentive to perception, to be present. Of course, you can’t do this all the time – it can be totally exhausting.

MJ: In an interview with Lois Patiño, we discussed the difference between internal and external time. He believed that we can extend our internal time by being really attentive of the beauty around us.

BR: Yes – and I think an important part of this is to become less conscious of the separation between the inside and the external world. We are the world and have always been the world; we’ve always acted within it and have always been acted upon by it. If we imagine that there is a split than we have trouble imagining ourselves to be part of a whole.

MJ: The world is one big organism.

BR: For sure. It’s like reality – you can break it down into different components, but it’s all there, always. The moment that we become attentive of the world is the moment when it really begins to vibrate.

MJ: In your film Ponce de Léon you use the quote: ‘I could do wonders if I didn’t have a body. But it grabs me, it slows, it enslaves me’. You seem to make a hard separation there between the internal world and the external world where we all have bodies.

BR: That bit of text was written by the main character in the film – a man in his 70s who was trying to escape the pain of being through a spiritual practice that involved astral projection (a willful out-of-body experience – ed.). It’s melancholic but it’s true: having a physical body is limiting. Of course, this doesn’t have to be a negative limit.

MJ: Because in the same time it makes us part of this world?

BR: Sure.

MJ: In your film we see a lot of scenes with communal rites in different forms. The noise concerts in the United States of course, but also rituals in non-Western cultures that involve singing and dancing together; for example the group of men singing together in Atlantis or the tribe that’s making music and dances all night in Greeting to the Ancestors. Are communal experiences a universal need?

BR: Yes – but let’s not forget the ritual of cinema itself: a place where bodies gather to collectively experience the same radical vision! When I was 22, I moved from Providence, RI to a small jungle village in South America where I worked as a development worker. It didn’t take too long for me to realize that the crazy noise concerts I’d seen in Providence had an essential commonality with this new set of Saramaccan animist ceremonies that I was attending there. Even as the cultural frame changes, the desire to be among other bodies persists. I started the Trypps series some time later – I wanted to use cinema as a divining rod to find an answer to the broad questions of collective movement and desire for communal experience.

MJ: Did you find any answers?

BR: I’m slowly developing an answer, but it’s still a bit vague to me. Humans are social creatures by nature; we have a clear drive towards collective experience, as if to compensate for the fundamental loneliness that comes with being human.

MJ: You recently visited French Polynesia to shoot a film. Can you tell something about what kind of film you’re making and your experiences there?

BR: I haven’t received the footage back so it’s still unclear to me what the film will be – but I can tell you something about my experience there. There was such a strange alignment of forces there, from French colonialism to nuclear testing to cultural revival to Polynesian tattooing – and I’m still trying to figure myself out in relation to all of it. Colonialism in particular sounds like a thing of the past – but being in the Marquesas (a group of volcanic islands in French Polynesia, ed.) for even a few hours makes it abundantly clear that Colonialism is a living, breathing thing. I bought a baguette, walked down Rue d’Joan d’Arc – on an island in the very middle of the Pacific Ocean! It’s a lot to comprehend.

MJ: It sounds like history plays an important role in understanding the place.

BR: To understand the present you have to understand the past. Colonisation – which is rarely anything but brutal – brings its own problems in understanding history. In French Polynesia, the native population was “accidentally” exposed to influenza and smallpox on numerous occasions; the survivors were subjects of Christian missionary work. Marquesan cultural practices were outlawed, the language atrophied and time did its work. When a cultural revival began to bubble up in the 1980s, a lot of the cultural knowledge of what-was came out of the work that anthropologists – so not ancestors! – did over a century prior… What was known and what was felt had been destroyed. In the Marquesas, material history in many ways became an unknown.

MJ: You said you didn’t see the footage yet. How does this process work for you, shooting a film and not seeing the footage for a while?

BR: There is so much time and energy and emotion wrapped up in the production of a film that, in order to begin to work on it, I have to build up enough distance so that I can experience it as an image. Not being able to see the material becomes a positive attribute because it allows the experience of filming to recede. Time passes and I’m able to approach the material as a set of images that are no longer tied so directly to the world that they came from. This isn’t so different from the experience that most of us have with selfies or snapshots, with the process of imaging ourselves – our disappointment with the picture of ourselves springs from a set idea of who we are, so much so that we’re rarely able to see the image for what it is. This separation of image and subject is critical in filmmaking, however – it allows me to advance, to recognize the image as the subject, to see what the most important things in my film are.