Dingen zonder dood

In Rotterdam vindt een verborgen gesprek plaats tussen de werken van Clementine Edwards in Roodkapje en Cecilia Vicuña in Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art; over het plastic afval dat we zonder rouwig te zijn schaamteloos hebben weggegooid.

Over Clementine Edwards & Cecilia Vicuña

Originele tekst ‘Invisible Yet Indispensable’ van Adam Patterson te vinden onder de vertaling

Een greppel kan fungeren als toevluchtsoord, begraafplaats of schuilplaats voor dingen die niet verdwenen of vergeten zijn. Toen ik jonger was en ontevreden met mijn seksualiteit maar tamelijk homoseksueel, gooide ik mijn ontevredenheid in de greppel in mijn achtertuin. Ik wilde af van dat ingewikkelde ding dat zweefde tussen plezier en schaamte. Waarom ik het in de greppel gooide en niet gewoon in de prullenbak? Ik wilde niet het risico lopen dat iemand anders ermee geconfronteerd zou worden, het was tenslotte van mij; het was me dierbaar, iets dat ik intiem gekend en vastgehouden had. En dus gooide ik het in de goot. Zodat ik het veilig kon bewaren, het als een geheim tussen de bomen, de greppel en mij verborgen kon houden.

Ik weet dat het niet zal vergaan; het ligt er nog steeds, verborgen onder kreupelhout met een zeer dreigende en obscene glimlach. Het soort glimlach gedragen door dingen die blijven bestaan, dingen zonder dood, dingen die niet kunnen worden weggegooid.

In Rotterdam vindt een verborgen gesprek plaats tussen de werken van Clementine Edwards in Roodkapje en Cecilia Vicuña in Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art; over het plastic afval dat we zonder rouwig te zijn schaamteloos hebben weggegooid.

Snoepverpakkingen, suikerklontjes, gedroogd zeewier, schelpen, poppenhuisonderdelen, Disney-prinsesstickers, veiligheidsspelden en andere glimmende, glanzende dingen nestelen zich in de studio van Edwards zoals in de schuilplaats van een ekster. Zwerfvuil is niet het juiste woord – de materialen zijn verzameld met de tederheid die nodig is voor het bouwen van een zandkasteel. Alle elementen die hier samenkomen zijn onderdeel van een voortdurende stroom sociale uitwisselingen. Ieder object is verzameld door te spelen met en te zorgen voor materialen die anders als afval worden beschouwd. Plastic hoopt zich op, het kan het niet helpen. Iedere uitwisseling waar het onderdeel van uitmaakt, laat een spoor achter op zijn oppervlak en zorgt voor sociale lading. Elk fragment resoneert met hoe vaak en op welke manieren het is veranderd en verplaatst. Of anders gezegd, elk voorwerp is makkelijk te beïnvloeden door elke uitwisseling waarin het zich bevindt; het wordt gevormd door de kenmerken die het via uitwisseling krijgt toegekend.

Wetende dat dingen breekbaar zijn en hun fragiliteit niet als vanzelfsprekend wordt beschouwd, brengt Edwards de samenkomst tussen de materialen als een teder spel. Elk materiaal vraagt stilzwijgend en open: “Hoe ga je met mij om? Welke zorg kun je dragen?” Niet alleen aan de kunstenaar, maar ook aan de kijker, de surveillant, de verwerker, de curator, de ruimte en alle andere variabelen die mogelijk in contact kunnen komen met het materiaal. Ik vraag me af of het plastic dat in mijn leven aanwezig is geweest, ooit is achtervolgd door een gevoel van wegwerpbaarheid, terwijl het altijd werd weggegooid zonder enige vorm van bezorgdheid over de toekomst van de wereld.

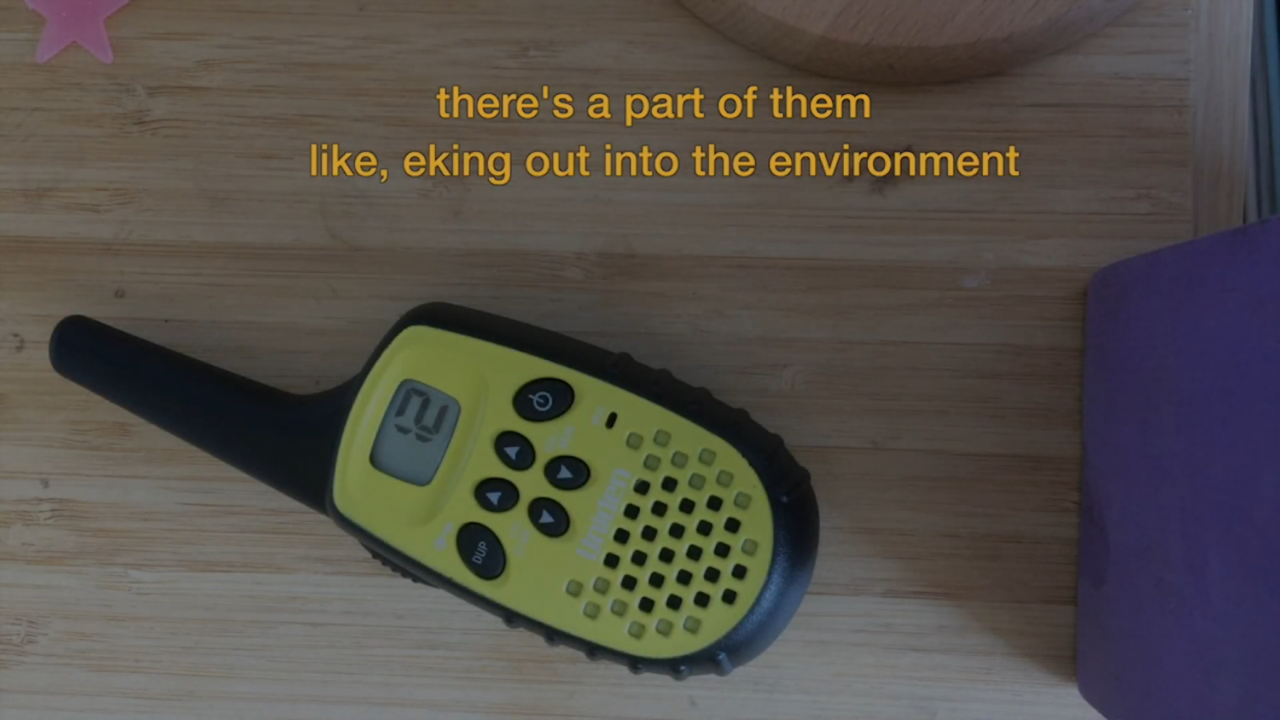

Het volgen van Edwards’ werk door de lens van haar korte film, Material as Kin (2019), dwingt je om je eigen relatie tot het plastic zowel binnen als buiten je lichaam te herzien. Tijdens een zwerftocht door een nationaal park en een verwerkingsplaats van plastic, overdenkt Edwards de wens verwantschap te creëren met tastbaar, aards materiaal. Drijvend tussen de natuurwandeling en de plastic installaties met de onbetrouwbaarheid van een dagdroom, kraakt een speelgoed walkie-talkie waaruit Edwards’ stem klinkt; de kunstenaar bewoont een onwaarschijnlijke plastic gastvrouw. De stem is gefascineerd door “al die wrijvende microdeeltjes” van plastic die zich onzichtbaar verspreiden en gedijen in zowel ons lichaam als onze omgeving, een menselijk maar onmenselijk nageslacht dat ons zeker zal overleven. Material as Kin geeft ruimte om na te denken over plastic voorbij het wegwerpbare karakter van het materiaal. De video bouwt voort op de essentie van onze verbindingen met dit hardnekkige materiaal: hoe kunnen we er zorg voor dragen buiten de gebruikelijke grenzen van onze aandacht? Het redden van plastic, het hergebruiken van dit materiaal, is dan ook het erkennen van dit ding waarmee we een ingewikkelde relatie hebben opgebouwd; een verwaarloosd deel van onszelf dat de moeite waard is om voor te zorgen.

Plastic hoopt zich anders op in Cecilia Vicuña’s Precarios (doorlopend). Vicuña worstelde zich door een struikgewas van aangespoeld puin dat zich aan land bevond, zoals doelloze kwallen op het droge. Daar, op het strand, begon ze haar serie kwetsbare objecten samen te stellen. Drijfhout, een versleten vislijn, verlaten schelpen, gezouten speelgoed en naamloze plastic scherven komen samen in zachte mismatches. Net als bij Edwards markeren de materialen van Vicuña talloze sociale uitwisselingen. Toch maken deze exemplaren, die mijlen langs en door de getijden reisden, indruk op de ervaringen die plastic doorstaat tijdens zijn circulatie over de planeet. Net als de gruwel van de rioolwaterzuivering, keren de dingen waarvan we dachten dat we ze weggooiden bijna met wraak naar ons terug. Als je Vicuña’s Precarios ziet, kun je het plastic horen ritselen met de vraag: “Herinner je mij nog?”

Vicuña toont plastic afval als delicate, organische materie. Het voelt als een poging verantwoordelijkheid te nemen voor deze merkwaardige, onsterfelijke substantie. Hoewel het in staat is af te breken maar nooit volledig verdwijnt, leidt de onsterfelijke aard van plastic tot problemen en maakt het de oorspronkelijke kennis, waarden en werelden die het werk van Vicuña informeren, gecompliceerd. In een praktijk die zo’n belangstelling toont voor de verbintenissen tussen leven en dood, blijft plastic een onverenigbaar figuur dat het fundament van het werk doet wankelen. Het achtervolgt ons met zijn vasthoudendheid, waarmee het een breuk met onze eigen vertrouwde opvattingen over wat het betekent om te leven en te sterven, opwekt. Hoe hardnekkig, onverzoenlijk of vreemd de aard van plastic ook lijkt te zijn in relatie tot onze eigen gevoeligheden, zijn prominente rol in deze werken smeekt er om na te denken over de vraag waarom we zo snel die ongrijpbare dingen welke begrip gemakkelijk of comfortabel ontwijken, kunnen verbannen.

Voor haar solo-tentoonstelling Sweetheart heeft Edwards kleine ruimtes op palen gevormd. De lichtste ademhaling zou hen kunnen ontwortelen. Terwijl ze haar handen voorbereidt om ze op te vangen, demonstreert Edwards het kantelen en dat triggert mijn geheugen. Ten eerste word ik herinnerd aan een windvlaag die alle Precarios van Vicuña deed instorten toen iemand tijdens de installatie een nabijliggend raam opende. Daarnaast moet ik denken aan Vicuña’s eerste Precarios die kwetsbaar aan de kustlijn wachtten op de juiste golf om op mee te drijven. Ook word ik ernstig herinnerd aan de huizen op palen in de Bahama’s en de passage van orkaan Dorian. Hoewel palen dienen om de komst van stijgend zeewater dat tot overstromingen leidt te dwarsbomen, zijn de orkanen sterk genoeg om de menselijk veiligheidsmaatregelen te overtreffen. Het heden lijkt te wachten op de juiste golf of de lichtste ademhaling om te worden meegesleurd.

De taal die de laatste tijd rond het Caribisch gebied wordt gebruikt, evenals in andere regio’s aan de frontlinie van de klimaatcrisis, bevindt zich ergens tussen onzichtbaarheid en wegwerpbaarheid. Ook de rest van de wereld is bezorgd maar houdt het daarnaar handelen op afstand. We willen niet toegeven dat we het zo ver hebben laten komen. Een gevoel van verwantschap met plastic voelen, kan betekenen dat je je stilletjes afvraagt waarom je het zonder aarzeling hebt weggegooid. Terwijl je nadenkend knielt om de precaire, kleine sculpturen van zowel Vicuña als Edwards, op hun schaal te ontmoeten en zorgvuldig hun geringste details te waarderen, moedigen de werken een zorg aan voor de nietigste delen van onszelf. De meest nietige delen van een gedeelde wereld en een gedeeld heden. De werken leggen de nadruk op de rouw om de verloren verbindingen en relaties met de dingen die we hebben weggegooid. Laten we manieren vinden te leven, te koesteren en vast te houden aan die dingen die ons niet zonder gevecht ontglippen. Hoe klein, hoe bescheiden, hoe onzichtbaar ook, ze zijn er en ze zijn zeker niet overbodig.

/

Invisible Yet Indispensable On Clementine Edwards & Cecilia Vicuña

The gully—a refuge, burial or hiding place for things neither gone nor forgotten. When I was younger, less at peace with my sexuality but still altogether rather queer, I threw something into the gully at the end of my backyard. I wanted to get rid of it—this complicated thing conflicted between pleasure and shame. And why the gully—why not just the garbage? Well, I didn’t want to risk anyone else handling it—it was mine, after all; at once, evidence that would out me and, otherwise, something precious to me, something that I had known and held most intimately. So, into the gully I chucked it. To keep it safe, to keep it hidden, its disposal would signify a confidence between me, the trees and this black rubber trinket.

I know it will not degrade, decompose or disappear—it still lays there, hidden in the undergrowth, wearing a most menacing and obscene smile; the kind of smile worn by things that persist, things without death, things that can’t be thrown away easily.

A subliminal conversation is being whispered across Rotterdam, between the works of Clementine Edwards at Roodkapje and Cecilia Vicuña at Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art; a prompt to recall the plastic castoffs we don’t take the time to grieve.

Candy wrappers, sugar cube boxes, dried seaweed, shells, dollhouse parts, Disney princess stickers, safety pins and other shiny glossy things litter Edwards’ studio like a magpie’s hideaway. Yet, ‘litter’ is not the right word—each material rests neatly and gently and the works are assembled with the caress needed of a sandcastle. Everything here accumulates as an ongoing series of social exchanges. Each token and its potential combinations is sticky with special attentions and attractions garnered from playing with and caring for materials otherwise deemed trash. Plastic accumulates—it can’t help doing this. And each relation it becomes part of, each hand it passes through, each exchange it contracts leaves a mark on its surface and its social charge. Each scrap resonates with how much and in what ways it has changed and moved. Or, to put it differently, each piece is vulnerable and impressionable to every exchange it may inhabit; it is all still being characterised.

Knowing things can break and not taking fragility for granted, Edwards locates the assemblage and installation of her works halfway between tenderness and play. Each work and its material asks, implicitly not punitively, “How will you handle me? What care might you be able to take?” — not only in the artist’s hands but between the viewer, invigilator, handler, curator, the space and all other variables it might come in contact with. I am left to wonder whether the plastic of my life has ever felt haunted by a sense of disposability, by all the times it’s been thrown away without a worry in the world.

Following Edwards’ body of work through the lens of her short film, Material as Kin (2019), pushes you to reconsider your own relation to the plastic both inside and outside of your body. A ramble between a national park and plastic rumination, Edwards contemplates a wish to make kin with a variety of grounding tactile materials. Drifting in and out between the nature walk and plastic montages with the slipperiness of a daydream, a toy walkie-talkie crackles and speaks in Edwards’ voice, the artist inhabiting an unlikely plastic host. The voice is fascinated by “all these fricking microparticles” of plastic spreading out and thriving invisibly in both our bodies and our environments, a human yet non-human offspring that will certainly outlive us. Building on the substance of our connections with this persistent material, caring for it beyond the usual limits of our attention, no longer believing there might be a way out from the plastic beds we’ve made for ourselves, Material as Kin lends room to think of plastic beyond ideas of disposability. Salvaging plastic, then, is to acknowledge this thing with which we have been complicated; a neglected part of ourselves that might be worth caring for.

Plastic accumulates slightly differently in Vicuña’s Precarios (ongoing). Wading through a thicket of washed up debris that finds itself ashore with the aimlessness of jellyfish, Vicuña first started assembling her Precarios on the beach itself. Driftwood, worn fishing line, abandoned shells, salted toys and nameless shards of plastic come together in tender mismatch. As with Edwards, Vicuña’s materials mark countless social exchanges and mutations. Yet, these bits and pieces, journeying miles along the tidal drifts impress the untellable lengths of experience that plastic continues to endure in its circulation across the planet as well as the journeys it has yet to make. Like the horror of resurfacing sewage, the things we thought we threw away return to us almost with a vengeance. Seeing Vicuña’s Precarios here, you can almost hear the plastic in them rustling the question, “Remember me?”

Vicuña’s incorporation of plastic waste into a practice of mostly delicate organic matter feels like an attempt to account for an uncannily immortal substance. Though capable of breaking down but never truly disappearing, the deathless nature of plastic troubles and complicates the indigenous knowledge, values and worlds informing Vicuña’s work. In a practice so concerned with the contracts to life and death, plastic remains as an irreconcilable figure seemingly shaking the foundations of the work. It haunts us with its own persistence while prompting the tremble and rupture of our own familiar understandings of what it means to live and die. However persistent, irreconcilable or queer the nature of plastic may appear in relation to our own sensibilities, its prominence in these works begs the question as to why we might be so quick to exile those elusive things that evade easy or comfortable understanding.

Preparing for her solo exhibition, Sweetheart, Edwards has been assembling tiny rooms on stilts. The lightest breath could uproot them. Readying her hands to catch it, Edwards demonstrates and blows over one of these precarious worlds and the topple triggers my memory. I’m first reminded of a gust of breeze collapsing all of Vicuña’s Precarios when someone opened a nearby window during installation. I’m then reminded of Vicuña’s first Precarios waiting vulnerably at the shoreline for the right wave to come along. And I’m gravely reminded of the houses built on stilts in The Bahamas and the passage of Hurricane Dorian. Though stilts serve to thwart the rise of floodwaters, the mutated efforts of climate-queered hurricanes have proven too much for the once reliable safety measures taken in the Caribbean. The present and our once familiar ways of life just seem to be waiting for the right wave or the lightest breath to come along.

The language used as of late around the Caribbean, as well as other regions at the frontline of climate crisis, sits somewhere between invisibility and disposability, as these relate to the rest of the world’s concern. Invisibility and disposability; qualities plastic is often condemned to share. To feel a sense of kinship with plastic might be to softly wonder why you are being thrown away without hesitation. Reflecting on both Vicuña and Edwards’ precarious little sculptures, kneeling down to meet them at their scale, looking slowly and carefully to appreciate their slightest details, not overstepping so as to avoid blowing them over, the works encourage a practice of caring for the smallest parts of ourselves, the tiniest parts of a shared world and present. It is to grieve those lost connections and relationships with the things we’ve thrown away and finding ways of living with, cherishing and holding onto those things that won’t let us go without a fight. However small, however invisible, they are here and they are certainly not dispensable.