The sea as metronome: estrangement and reconciliation as experiences of time

In a series of publications and public programs, Mister Motley and ArtEZ Studium Generale explore the connections between time, labour and ecology, in collaboration with students, artists, writers, academics and thinkers. In the opening essay of this series, Laure van den Hout looks at nature as our first experience of time that is shaped by estrangement and reconciliation. Think of the moon and the sun – moving closer and further away -, think of dusk and dawn, ebb and flow. Analyzing water and the different shapes in which it presents itself to us, Van den Hout shows us that you cannot dictate the state you’re in at a given moment; that productivity, to the extent we are used to it, is more likely a state we force upon ourselves. That social engineering has limits.

Translation by MM Garr.

In her extraordinary book The Sea Around Us, marine biologist Rachel Carson writes on the fascinating depths from which we humans came. Though the book was first published in 1951, it remains surprisingly current. Her holistic view of nature, and the predominantly negative influence humans have on it, come out in every word. One passage in particular has stuck with me, in which Carson cites a private encounter with the sea as the moment when a person realizes they are only part of a much larger whole, a whole where their illusion of social engineering is no more than pretense:

“He [i.e. humans] cannot control or change the ocean as, in his brief tenancy of earth, he has subdued and plundered the continents. In the artificial world of his cities and towns, he often forgets the true nature of his planet and the long vistas of its history, in which the existence of the race of men has occupied a mere moment of time. The sense of all these things comes to him most clearly in the course of a long ocean voyage, when he watches day after day the receding rim of the horizon, ridged and furrowed by waves; when at night he becomes aware of the earth’s rotation as the stars pass overhead; or when, alone in this world of water and sky, he feels the loneliness of his earth in space. And then, as never on land, he knows the truth that his world is a water world, a planet dominated by its covering mantle of ocean, in which the continents are but transient intrusions of land above the surface of the allencircling sea.”

Carson writes wonderfully about the most unimaginable things. About fur seals with bones in their stomachs from a species of fish that humans have never seen alive. About why warm-blooded mammals like baleen whales seem to be immune to caisson disease (“the bends” or decompression sickness), even though they ostensibly make vertical dives into the depths and return to the surface “almost immediately”. She attempts explanation, but more so tries to celebrate wonder, the wonder that leads some to study the reason behind it, but also the wonder that is so real in and of itself.

It is wonder that softens us to our surroundings, makes us look harder, makes us aware of how necessary to our own lives all life around us is. Which, in short, makes us humble. In this wonder, Carson returns again and again to time as a guiding element. First, in the opening chapter “I Mother Sea”, when she describes how the seas were created, how the now-natural rhythms developed, how the sun and moon play an important role in them, just as they also help determine which organism lives where.

But also more subtle, and more conceptual: how there are depths to which we can hardly, if at all, descend, places where we assume nothing lives (here, of course, a parallel can be drawn with the depths in the other direction: space). Our imagination of what is feasible takes our own conditions of existence as a frame of reference – logical, of course, but also frequently wrong. At the bottom of the deep sea, devoid of light, live worms.

In “On time” in her book Artful, Ali Smith writes about someone whose partner has passed away. She walks through her home, the home she shared with her partner, sees how their books are intermingled on the shelves (“the most faithful act of all, mix our separate books into one library”), picks one out. It is Dickens’ Oliver Twist. She hasn’t been able to read since the loss – it has been a year and a day. And she thinks back to when she last read the book now in her hands:

“I’d not read Oliver Twist since, oh god, when? way before we even first knew each other, I’d had to, for university, so that made it thirty years. That gave me a shake. A twelvemonth and a day can arguably be called short, but thirty years? How could thirty years be the blink-of-an-eye it felt? It was the difference between black and white footage of the Second World War and David Bowie on Top of the Pops singing Life on Mars; it was the size of a grown woman with four children, one of them nearly old enough, if the woman started very early, to be doing A-levels. They definitely weren’t called A-levels anymore.”

There’s a dilemma, though, that she must face before she is to read again. The chair she wants to start reading in belonged to her partner: “But it was your chair, this chair, even though we’d bought it on my credit card (and it still wasn’t paid off; how unfair that a chair we saw online and bought on a credit card and had delivered in a van would, could, did, last longer than us). And we’d had that argument about moving it several times and you’d always won that argument.”

Her partner’s chair, which she didn’t think was in the right spot. Not able to catch the right light, too much of a draft, too far from the desk in any case. Would moving it now be an act of disloyalty? She does it. With brute force and rolled-up rugs as a result. It feels good. After a few minutes, we hear her thinking, “In fact I just managed a whole ten minutes there without thinking of you once, I thought, then I turned back to the book. Then I looked up over the top of the open book because it sounded like someone was coming up the stairs. Someone was. It was you.” Disheveled hair, covered in dust and debris, her eye sockets black.

A conversation between them follows, about all manner of things: they bring up habits, they cite literature, tell stories of their shared past. At one point, the protagonist thinks, I should offer her tea, and then realizes that the partner on the couch is a figment of her imagination. This does not, however, make this being with her partner stop; it leads to a refreshing insight: “I could offer a figment of my imagination tea if I wanted.” Ali Smith has lavish praise for the wonderous power of imagination: “Oh, the imagination was fantastic: mine didn’t just make up some place you’d been, it even made up words whose meanings I didn’t know – which was exactly what it had been like, to live with you. In fact when I went through and tried to look up that word in the dictionary I couldn’t find a word like it. So the imagination was even more amazing than I’d given it credit for.”

That our perception of time need not coincide with actual elapsed time, we feel most when emotions are at their highest. As in “On Time”, when a loved one dies. The period after can feel timeless, like a vacuum, or hard to put a timeframe around. Are the days endless? Do they fly by? Sometimes both, on the same day. Thinking back to when someone died, the calendar time that passed often does not match the felt time that passed. For example, I sometimes hear myself thinking out loud: six years, how can it have been six years already. It is incomprehensible, even though a lot has happened in that time, which means that when I do focus in on it, I really feel the length of those six years. It’s just different perspectives to look back from, with their corresponding experiences and emotions. Everyone’s subjective and personal time differs, therefore, from the time that is propelled by clocks, and perhaps within that subjective time there is occasionally another dissimilarity, depending on the perspective you take for that personal experience of time. And under the influence of intense emotions, this difference may be larger or smaller, because those emotions can considerably stretch or compress our experience of time. So thirty years can feel like an instant, literally a blink of an eye.

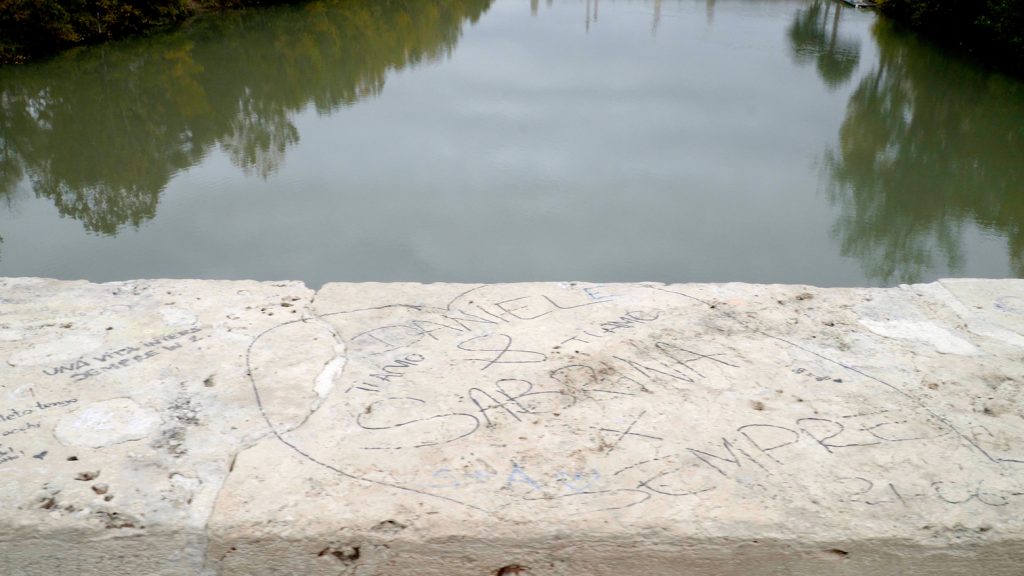

From a bridge, I look out on a river. The water is calm. Steady flow. Maybe that’s what’s called “trickling”. The natural stone sides of the bridge display names, sometimes intersecting with hearts pierced by arrows, professions of love, promises.

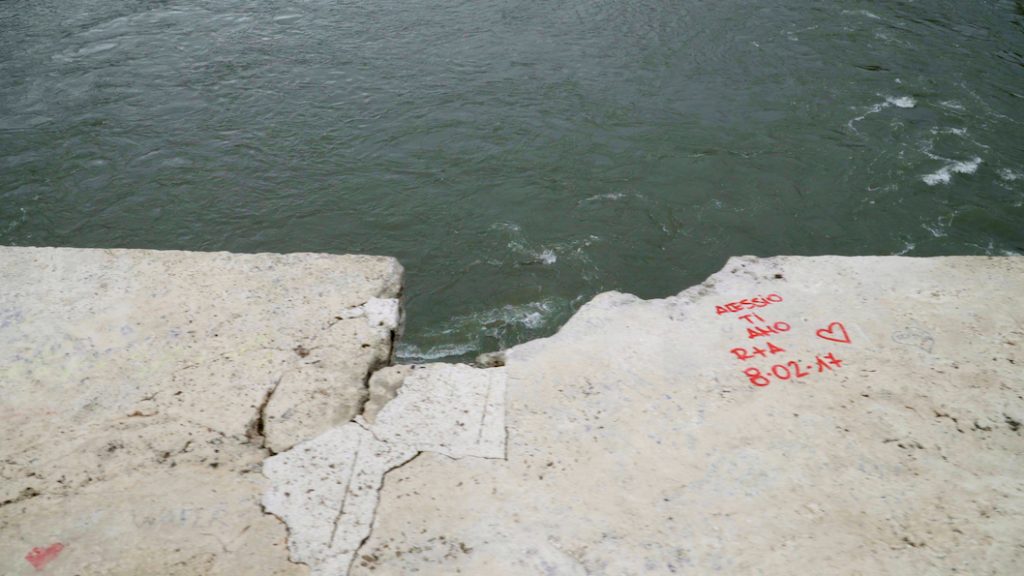

Again I see a river. Again from a bridge. The same river, the same bridge. This time the water is rough. Foaming at the mouth. A fast current. The natural stone sides of the bridge display names, hearts, professions of love, promises.

I can take in these two rivers, that are and are not the same river, in a single view. I see this as a visual translation of Heraclitus’ “no man ever steps into the same river twice”. It makes my thinking nimble: what a simple but incredibly effective way to represent time. Ambiguous, a snapshot, a reality of that exact time, never the same, and an infinite loop.

On the stone sides: “Per sempre”. “Ti amo”. Some messages are scratched into the stone; others calcified in permanent marker. Red. Black. Wear-resistant for a time – surely not forever. Ironic.

I saw these two rivers that are the same river in Marijke van Warmerdam’s exhibition Then, now, and then at the Landhuis Oud Amelisweerd, where I went on the last Saturday it was open, in November 2022. Sure – I wanted to see this exhibition right away, but I didn’t have time. And that was true, but only now as I write this do I understand its irony.

The work consists of two large screens side by side, free-standing displays installed in a room, on which two shots of the same river – but in different states – can be viewed. This makes you look more closely, searching for the constants where there is overlap and for what is different. Like the water’s current, the films go on and on, in a loop. The water goes around, but not in the same artificial way as the hands of a clock.

For a moment I feel lighter. We can’t experience the different currents at the same time, but we can imagine it, or fathom it, if we’ve seen it, like how this artwork makes me envision it, giving me a metaperspective that I cannot myself occupy, at least physically, but can adopt, spiritually.

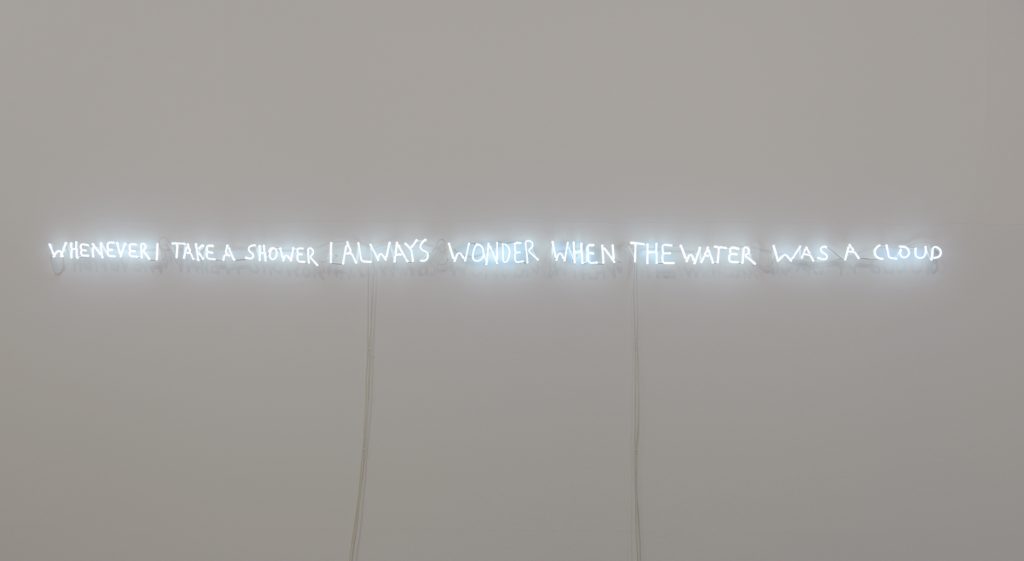

Before humans made clocks, there was already a clock, and still is. That of nature, the moon, the sun. Which influence the tides. The link between water and time, you see, is a primordial one. Unlike our clock time, which more than anything else is a mold into which we all try to squeeze ourselves, water has different states. It can transform. Water is not a single thing; it is briefly something and potentially everything. “Whenever I take a shower I always wonder when the water was a cloud,” as artist David Horvitz’s neon work aptly puts it.

Nature was our first clock. The rhythm of the sun and moon: for ages we needed no more than to know when the sun rose and when it set. Those were the productive hours, the hours when there was something to see, when work could be done. You more or less knew when it was time for the harvest, but you could not set a clock to it; nature does not allow itself to be forced into such a granular record of time. After all, it depends on so many variables: temperature, rainfall – to name a few.

Humans developed clocks based on nature’s rhythms – day and night, the seasons. First by using a stick in the ground, whose shadow indicated time. This is how sundials developed; one of the first – as far as we know – comes from Egypt and dates back to 1500 BC. People also used water clocks: you could read how much time had passed based on how much water had run off, like how an hourglass works. Sensible, since a sundial is useless if there’s no sun or on a cloudy day. But also impractical, because water can freeze – and so, therefore, can time.

With the advent of the industrial revolution, humans gradually managed to “conquer” time: time began to determine the day’s rhythm in the workplace, how long workers’ breaks were, how much they were paid (derived from how much time they had worked), and finally the amount of free time they got. In Tempo: Il sogno di uccidere Chronos (“Time: The Dream to Kill Chronos”, not yet translated into English), Guido Tonelli writes, “Humans, dreaming of capturing Chronos [the name the Greeks used to personify linear, measurable time], are dismayed to discover that in reality they have only made themselves captives.”

The cycle of water is a beautiful metaphor for what is missing from our current Western and predominantly capitalist understanding of time. It resonates with the cyclicality that lives in each of us: that you cannot dictate the state you’re in at a given hour; that productivity, to the extent we are used to it, is more likely a state we force upon ourselves. That social engineering has limits.

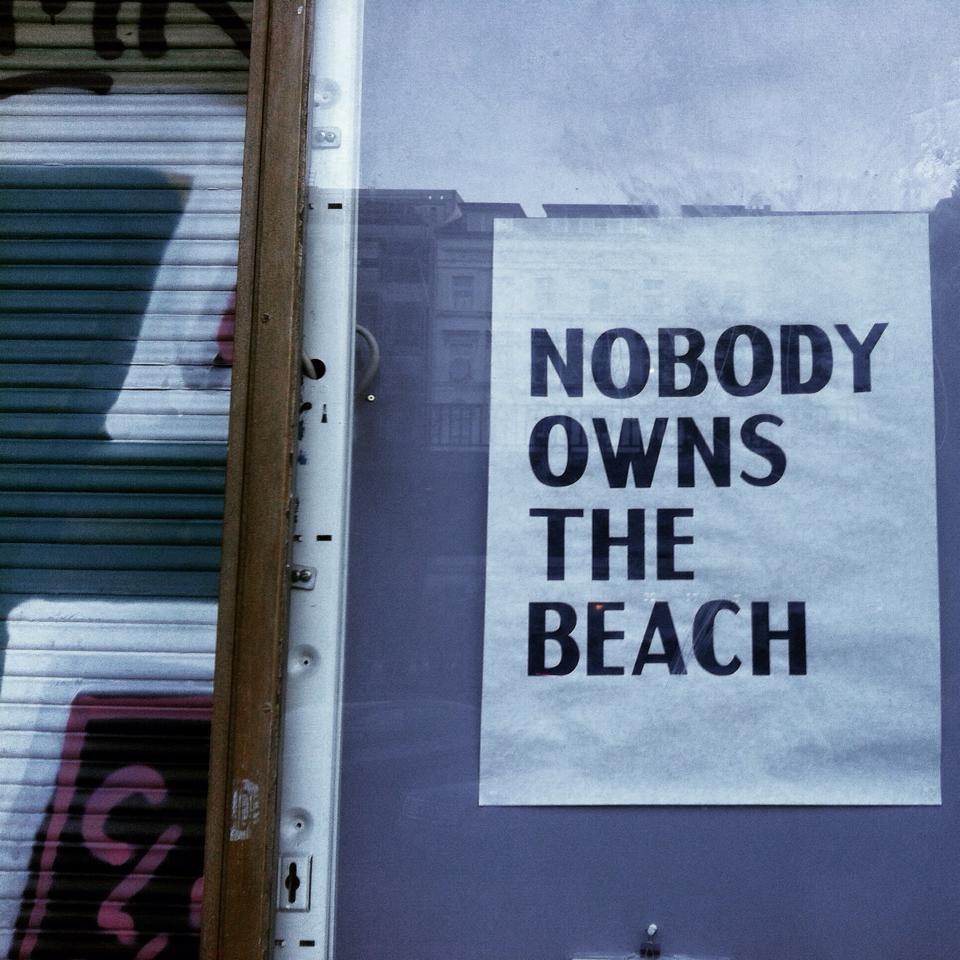

I was in Berlin a few years back, and there were posters scattered throughout the city that read “Nobody owns the beach”. I found these posters fascinating, in part because of what they said and the fact that they were purely typographical, but mostly because they were usually near posters trying to sell me something: a hair product, a new type of beer, a dating app.

My first thought with “Nobody owns the beach” was, of course nobody owns the beach, can you imagine? But when I started thinking about it, I couldn’t actually say how much nature really belongs to “itself”. Conceptualizing (cultivating) nature for capitalist gain is our status quo. What’s more, or maybe even by extension, nature is there for our recreation (an interpretation of “free time”, which that same capitalism spawned). Thus is nature conquered, it has utility, and we use it instead of listen to it – or its rhythms.

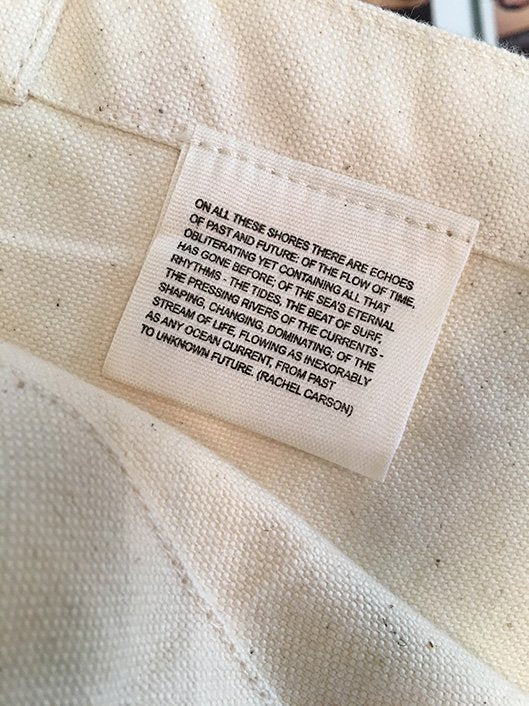

What I didn’t know at the time, but do now, is that these posters were by David Horvitz, and that he designed a tote bag with the same text. The tote bag, the bohemian bag that became cool, making the work a somewhat ironic commentary on capitalism. On the tote bag’s inner label is a quote from none other than Rachel Carson: “On all these shores there are echoes of past and future: of the flow of time, obliterating yet containing all that has gone before; of the sea’s eternal rhythms – the tides, the beat of surf shaping, changing, dominating; of the stream of life, flowing as inexorably as any ocean current, from past to unknown future.”

Time and transformation come up frequently in Horvitz’s works. His Nautical Dusk (2013) consists of a bell and a sign which reads:

Notice

For the current exhibition (from [Date] until [Date]) the gallery’s normal closing time of 6pm will change to the time of each day’s nautical dusk.

Today’s closing time will be at ________

I try to imagine how I would react if I came across this work in a gallery. I often think, ok, if I get to the gallery at 3pm, and they close at 5pm, then I still have two hours to look at everything. If the space closes earlier because nautical twilight has arrived, I would suddenly have less time to look at everything. The work is, as it were, an intervention: it puts everything on edge, a good way to make tangible how much hold time has on us and what that comes at the expense of, what it costs.

Horvitz wants to link the place, the situation, to our prevailing idea of time and to something that is always there with a rhythm of its own – nature. To make tangible how art in a gallery is part of the capitalist system, and he does so using only a bell, words, and a forced change of the closing time.

But also, with the dispersal of the “Nobody owns the beach” posters, the location where they hung (a large city) is synonymous with a place that is far from the beach or nature, or removed from it entirely. And suddenly it becomes clear – I would almost write “tangible” – how the two differ in rhythm and pace. Unnatural versus natural. Horvitz himself says, “A lot of my work is about reminding yourself that you are somewhere unique – in a spatial sense and a temporal sense. Imagine what it was like before time zones, when places had their own times. What time is it? Where exactly are we right now?” And about the other rhythms that determine our existence:

“To me, it is more interesting when something happens that you don’t expect. I really despise keeping a schedule because for me that ruins a day. You already define what you are doing at a certain time and place, and that day is no longer open for something unexpected to happen. A few years ago I did two connected shows at Jan Mot in Brussels and Dawid Radziszewski in Warsaw. The shows opened the day my friend Jenny gave birth to her daughter, so no one knew exactly when the opening would be. I wanted it to be unknown, to complicate the gallery’s calendrical system with the biological (and lunar?) rhythms of my friend’s body. I’ve always been amused when Brooklyn Botanical Gardens would have their Sakura festival and none of the cherry trees would be in bloom yet, or the peak blooms would be over. The gardens would have to schedule it a year in advance for various reasons, but a tree will bloom when it wants to bloom. In Japan, the moments the trees blossom is the moment you celebrate Sakura. You are on the tree’s schedule – it doesn’t follow your Google calendar.”

That we have the audacity to project our inclination towards social engineering onto nature’s rhythms is now more obvious than ever. Many of us perfectly ignore the signs we’re getting that the planet is in trouble and that we’re not doing enough to combat the climate crisis. The centrality we have given ourselves as humans is so pervasive that we actually think we can solve this problem without having to act on it now. The fact that our own lives depend on all life around us hardly seems to breach this veil.

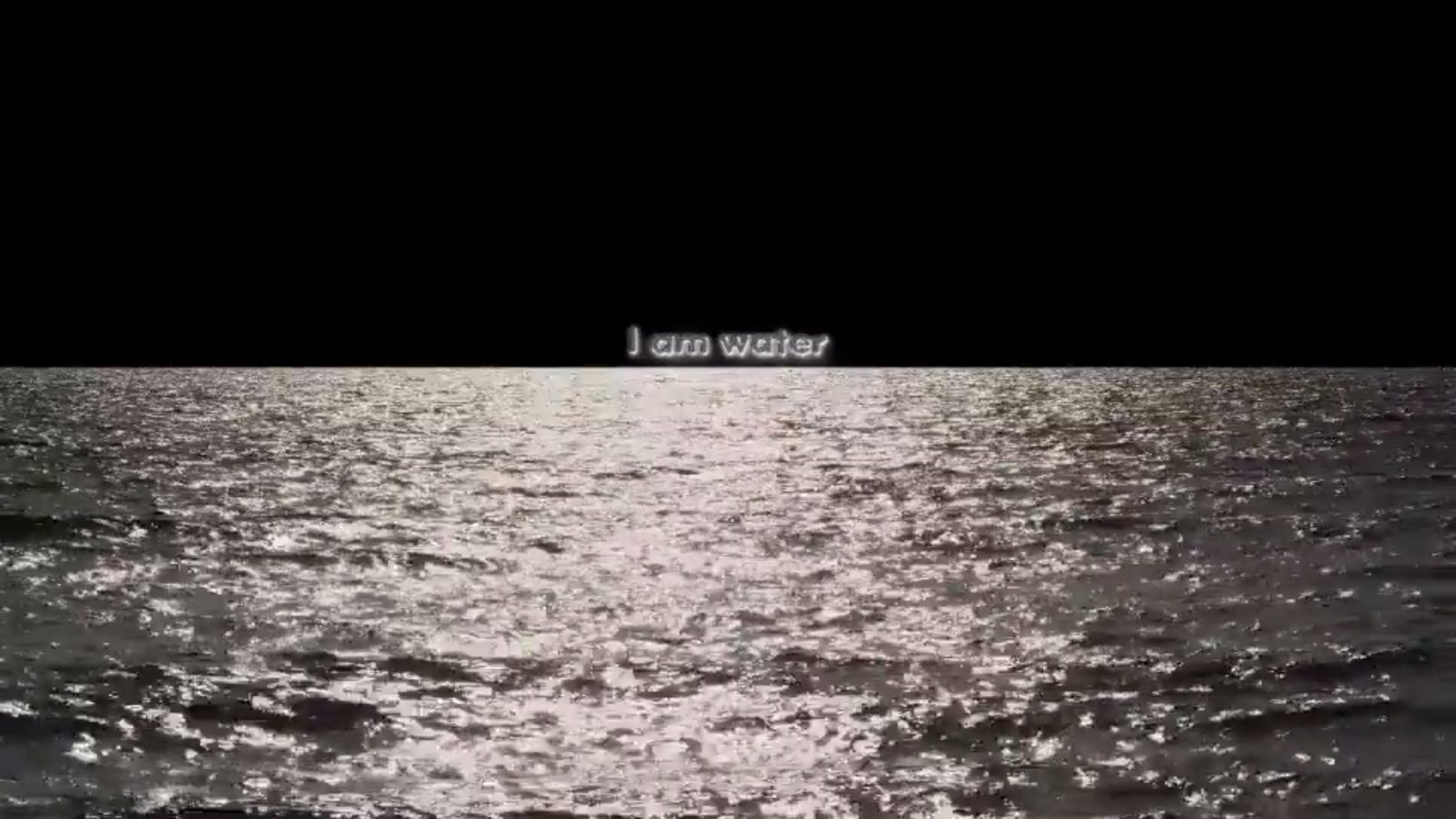

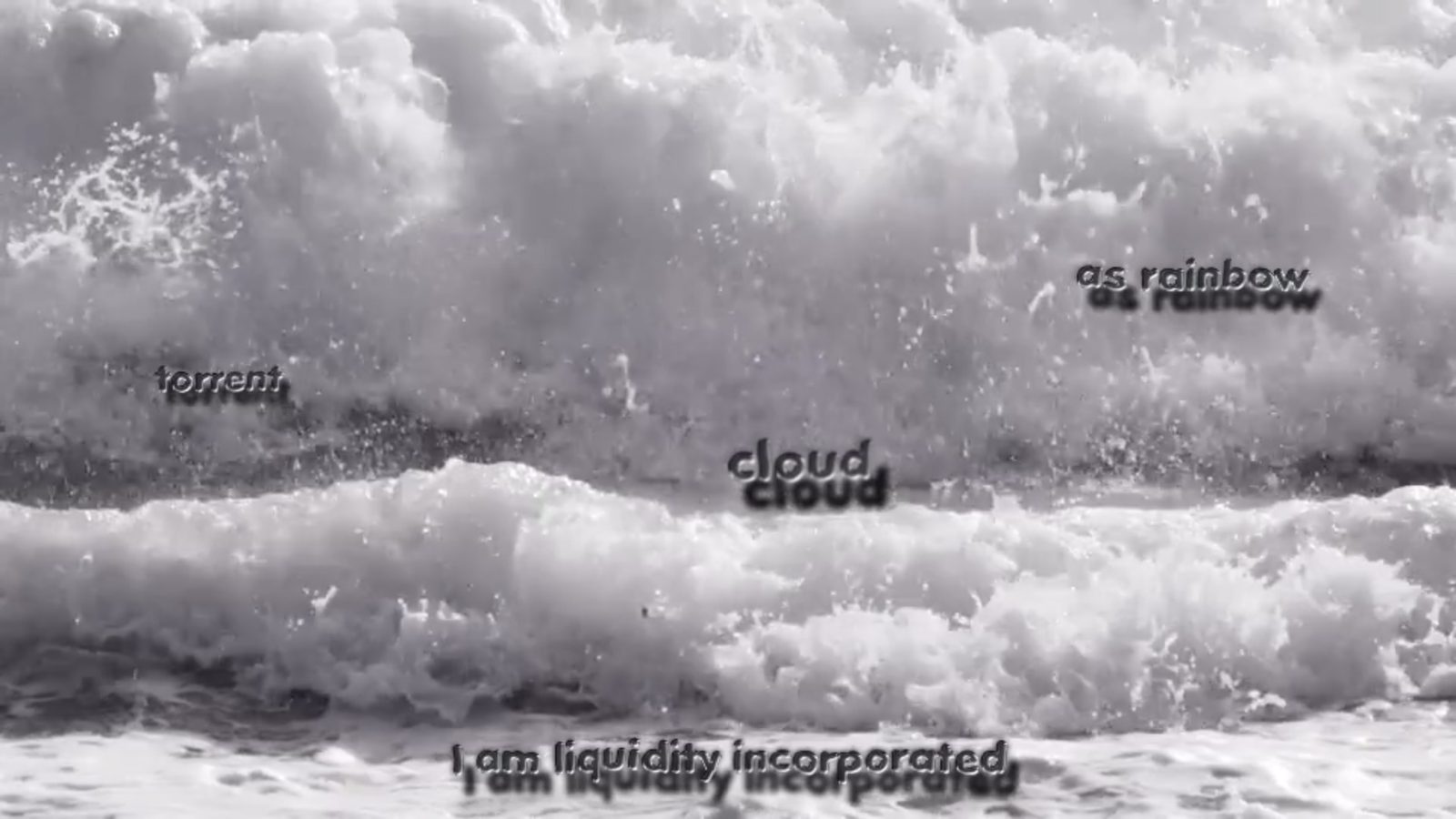

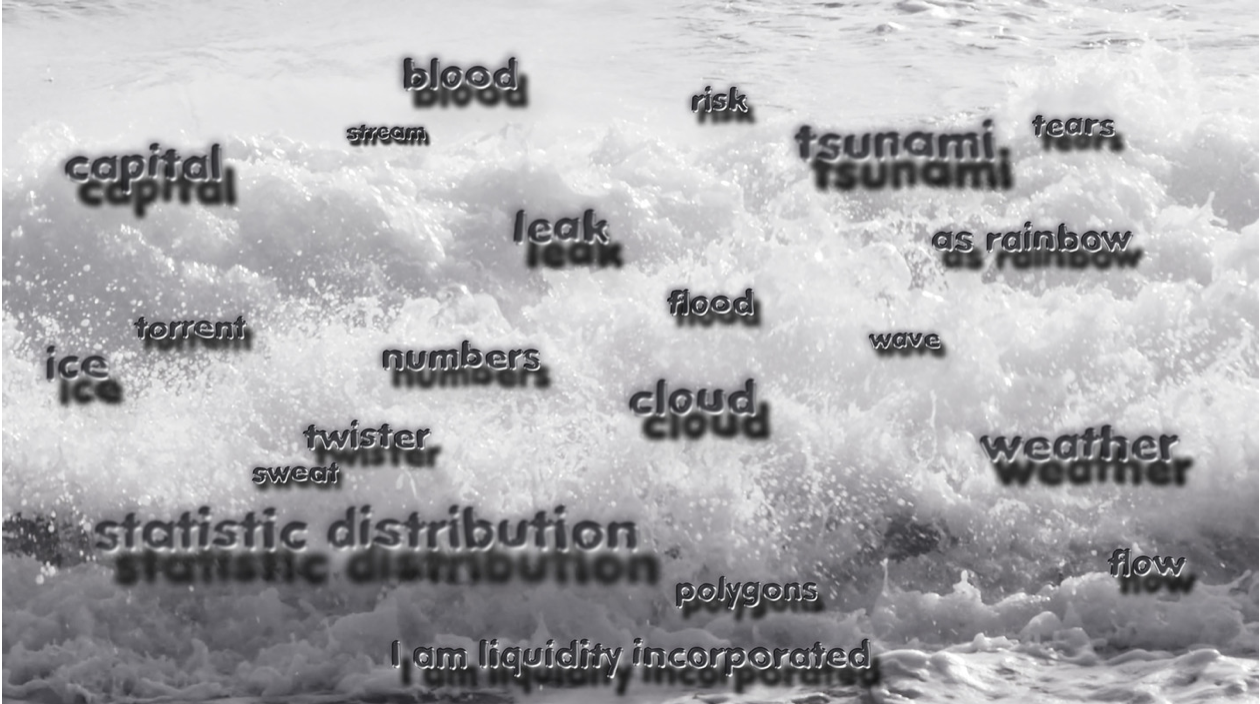

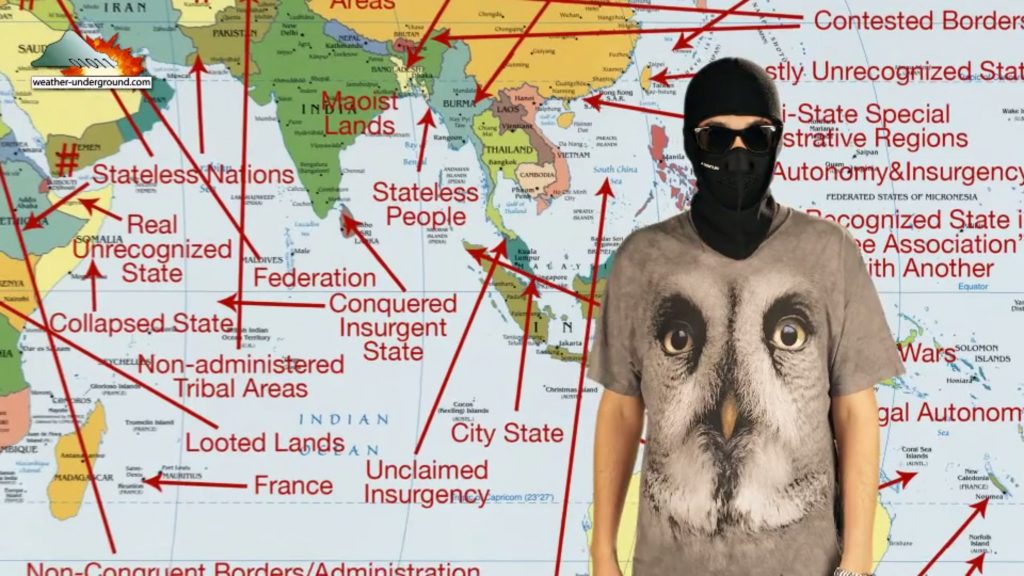

This far-reaching capitalization of nature in relation to our agendas – both in the literal and figurative sense – is further magnified in artist Hito Steyerl’s hallucinatory video work Liquidity Inc. Steyerl emphasizes the multiformity of water, the cycle, the different phases something goes through, the different versions something can be, the infinite combinations that can be made between ideas that initially seem unrelated. In the first minutes of Liquidity Inc., we hear a voiceover from the perspective of water. While “I am liquidity incorporated” is heard, words like “as rainbow”, “torrent”, “cloud”, and later “leak”, “flood”, “wave”, “tsunami”, “tears”, “sweat”, “ice”, “flow”, “weather”, “stream”, “twister” appear on the screen. In these forms, we can easily imagine ourselves as water.

Then more puzzling concepts follow: “polygons”, “numbers”, “capital”, “statistic distribution”, “risk”. But perhaps not so puzzling after all, since we have already noted that water and time are linked. And time is money. Liquidity Inc., like all of Steyerl’s works, is bizarre, stylistically multifarious, over the top, elusive. It is a complex visual essay in which, as a viewer, you are tossed to and fro. Which side are you really on? And which one is the morally correct point of view?

“Empty your mind. Be formless. Shapeless. Like water. You put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Water can flow, or it can crash. Be water, my friend,” the voiceover says. It sounds like an incantation. It also sounds cultish. Is being flexible and malleable a good thing? Or is it that very social engineering that seems beautiful, but is actually spineless? That spinelessness which polluting industry, governments and others benefit from because it ensures that we obey and stay on the treadmill? Steyerl interweaves this social engineering with the meaning of liquidity – fluidity and ability: “When you have liquidity, you’re in control.”

Malleability and flexibility are dangerously related but are rarely the same thing. Being flexible includes being able to adjust your point of view because, upon reflection, it turns out that you weren’t right after all, or new insights compel you to change direction. Malleability is being easily able to stay in line. Shifting when the winds shift. Leave it to Steyerl to turn that shifting on its head and offer instead an apt reflection on what belongs to whom in this world, and who can afford to be flexible. In the form of a weather report, Liquidity Inc. announces that there are trade winds, and people are blowing back into their homes, products are blowing back into their factories, factories are blowing back into their countries, countries back into their supposed origins. “Blowing people back into their past.” It’s a highly intelligent critique of the system, dressed in a lyrical jacket. “Weather is time.” “Weather is money.” “Weather is water.” This was never as true as it is now.

I think back to the words on the bridge in Marijke van Warmerdam’s work: per sempre. The Greeks believed that the ocean was an endless stream that flowed over the edge of the world eternally, marking the end of the known world. Beyond it the unknown, the uncharted. Let this myth be a metaphor: nature still knows so much that we have not yet discovered or unraveled. The “for all time” (per sempre) implicated in writing two names around a Cupid’s heart on the side of a bridge over a river is still most apropos of just that: water. It will always be there, but not where, when, and how we want. The water will be too high in places that cannot sustain it, and too low or absent in others – with all the consequences that entails.

We cannot step into the same river twice; a moment is not as easily engineered as we think. In “On time”, Smith’s main character thinks:

“You can’t step into the same story twice – or maybe it’s that stories, books, art can’t step into the same person twice, maybe it’s that they allow for our mutability, are ready for us at all times, and maybe it’s this adaptability, regardless of time, that makes them art, because real art (as opposed to more transient art, which is real too, just for less time) will hold us at all our different ages like it held all the people before us and will hold all the people after us, in an elasticity and with a generosity that allow for all our comings and goings.”

To me, this is a call for art – broadly speaking – to become our alternative “measuring instrument”, precisely in the sense Smith describes: when we return to a work we know, we experience who we are relative to our first encounter with that work. This development is not linear, but hinges on estrangement and reconciliation, as does everything in life. The moon, the sun: closer and then again further away, ebb, flow, dark, light. It makes one humble and resilient: returning to something you thought you knew, and experiencing that it has changed, that you have changed – but vice versa too, returning to something you recognize so well and still being touched by it. To do that again and again is a kind of quiet resistance, a way to keep feeding the idea of time beyond just capitalism’s notion of it: to keep making yourself aware that real growth is not just moving forward, but much more often means taking a step back, being able to change perspectives, staying flexible, rather than becoming malleable.

References

Carson, Rachel. The Sea Around Us. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Norton, Margot. “David Horvitz in conversation with Margot Norton.” CURA. magazine, no. 26 (Fall 2017): https://curamagazine.com/digital/david-horvitz/.

Smith, Ali. Artful. London: Penguin Books Limited, 2012.

Tonelli, Guido. Tijd. Een reis van vroeger naar later. Translated by Hans van den Berg. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij, 2022.